Pretty in Pink: The Feminine and the Male Gaze

,

Pretty in Pink: The Feminine and the Male Gaze

Part I: Of Orpheus and Eurydice[1]

Orpheus and Eurydice, Peter Paul Rubens, 1636

There are many stories told of Orpheus, but probably the best known concerns the death of his wife—Eurydice—on her wedding day. We know this tale from many sources, but most of them grow out of the myth as told by Roman poet Ovid in The Metamorphoses, 8 CE. Driven by grief, Orpheus travels to the Underworld and pleads with Pluto to release her. He does, with one condition—Orpheus must lead her out of the Underworld without seeing her before she is above ground. In his excitement, Orpheus turns to greet her when only he is above ground and loses her again, this time forever. Orpheus then wanders the world in grief, singing songs about his great love for Eurydice, until he encounters a group of Maenads—ecstatic female disciples of Dionysus—who tear him apart with their hands.

In John Berger’s The Art of Seeing (BBC, 1972), he discusses what has come to be known in the art world as “The Male Gaze.” “According to usage and conventions which are at last being questioned but have by no means been overcome—[in art] men act and women appear. Men look at women. Women watch themselves being looked at.” He’s not suggesting it’s right or even that it’s human nature. He’s saying that’s what we have to look at, what rich white men—mostly—wanted to look at. “Men look at women. Women watch themselves being looked at.”

In 1973, British film critic Laura Mulvey further developed the idea of the Male Gaze in her essay “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema” (Screen, 1975). It was “one of the first major essays that helped shift the orientation of film theory toward a psychoanalytic framework.”[2] According to Mulvey, “The Male Gaze is the way in which the visual arts and literature depict the world and women from a masculine point of view, presenting women as objects of male pleasure. The Male Gaze consists of three perspectives: that of the person behind the camera [ed. the director], that of the characters within the representation or film itself, and that of the spectator.”

In Ovid, men act and women disappear. Eurydice is missing for most of the 1006 words of the Theoi Classical Text translation (1922) and is never more than Orpheus’s “beloved bride.” There is no reference to a life before her wedding/death. She is a plot necessity. “So they called to them Eurydice, and she obeyed the call by walking to them with slow steps. So Orpheus then received his wife.” Later, as he exits the Underworld, “… he turned his eyes so he could gaze upon her. Instantly, she slipped away. He stretched out to her his despairing arms, eager to rescue her, or feel her form, but could hold nothing save the yielding air. Dying the second time, she could not say a word of censure of her husband’s fault; what had she to complain of—his great love? Her last word spoken was, “Farewell,” which he could barely hear, and with no further words, she fell from him again to Hades.”

In this case, the Male Gaze literally killed what it loved.

In Ovid, Orpheus’s argument with Pluto is not that she is his property or even his wife. It is that Eurydice’s death is a violation of natural law. As a young woman and new bride, her premature death has “robbed her of her best years.” It is for her sake—not his—that Orpheus argues for her return. He sings that he has tried to accept her death, but “Love won.” And—when his argument does not satisfy Pluto—he asks for her return as a gift for one whose love has been so strong that he has traveled even into the depths of Hades to rejoin her, and that “if the fates refuse my wife this kindness, I am determined not to return.”

February 6, 1986

[My therapist] Myrna asked today if I could remember the first time I was deeply moved by a myth, something that seemed connected to my life in some way, something I identified with, something I understood from the inside, more than just a good story. My answer was instantaneous. Orpheus and Eurydice. I knew those feelings even as a pre-teen when I first learned about them in Edith Hamilton’s Mythology. I still consider it a very meaningful love story. Myrna asked me to retell their story in my own words. I told her that Orpheus was a poet, a singer, who sang his songs to the lyre, so he’s the patron of all lyric poets, of whom I consider myself one. Orpheus fell in love with Eurydice, and they married. On her wedding day, she went out into the fields to gather her bridal flowers but was bitten by a poisonous snake and died because Pluto had a crush on her. When Orpheus found out she was gone, he was inconsolable and traveled into the Underworld to find her and bring her back to life. Orpheus sang of his love of Eurydice to the Lord of the Dead, who was so moved he agreed to release her, on one condition—that Orpheus would lead her back to the upper world, but he couldn’t turn around while she was still in the Underworld or the spell would be broken and Orpheus would lose her forever. When Orpheus gets back into the sunlight, he’s so excited he turns around to embrace her, thinking she’s right behind him. But she is many steps behind because one of her feet was bitten by a poisonous snake that killed her, and she’s still dead and walking slowly. So, he loses her a second time, and this time it’s his fault and his guilt oppresses him, and he wanders the world singing of Eurydice—and everyone and everything that hears his songs weeps—even the animals and stones, even clouds and mountaintops. I stopped there. That’s my favorite part. “How does Orpheus’s story end?” “He runs into some crazy Maenads who can’t hear him singing, who tear him into pieces and throw him in the river.” We sat in silence, Myrna looking at me sadly. “What do you identify with in that story, Randy?” I told her I knew that feeling of loving something out of reach. “But it’s a very sad story for a love story,” she said, and began to cry.

Part II: The French Lieutenant’s Whore

In 1969, the English novelist John Fowles published The French Lieutenant’s Woman, a “post-modern” novel in that it includes three different endings and other techniques designed to undermine the reader’s identification with the story as anything other than fiction rooted in an exploration of Victorian and modernist ideas of the feminine. Fowles claimed to be a feminist and the book to be a feminist novel, although this has been challenged—not only by feminist critics. More about that later.

In the book, a young man—Charles Smithson—is on his way to Victorian success. He is engaged to a “proper” (boring) young woman of his social standing, is in line to inherit a very successful family business, and his success and future are assured. But while out for a walk visiting his fiancée, he sees a cloaked woman with her back to him, standing desolately and dangerously at the end of a stone pier in a great storm. Rushing to her aid, he startles her and sees only her flashing eyes and long wild red hair before she disappears.

But something in this wild woman has sparked something inside him, and he can think of nothing else. He asks about her in town, where she does not even have a name, being referred to as “the French Lieutenant’s Woman” in proper company, and “the French Lieutenant’s Whore” and “Tragedy” in private. She is a “disgraced” domestic, and it is said she cared for an injured French sailor, who returned to his wife when he was able. Since then, she stands at the end of the pier every day, waiting—the townspeople say—for his return.

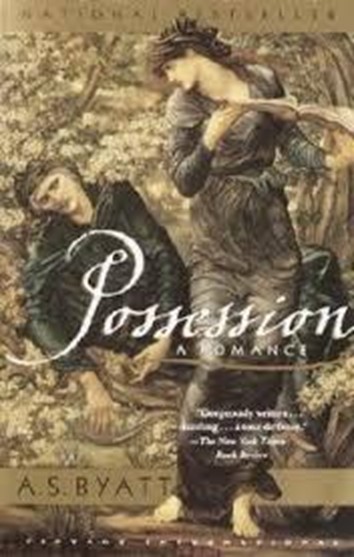

I was 36 years old in August 1990, and shopping in Shakespeare and Co., a bookstore in Paris, when I was startled by the painting on the cover of A. S. Byatt’s Possession, which had just won the Booker Prize. I had never heard of Byatt or the book, but I was intrigued that it had been written as a response to The French Lieutenant’s Woman. It also borrows Harold Pinter’s conceit from the film by portraying two couples—one Victorian (based on Christina Rosetti and an amalgam of poets Robert Browning and Alfred, Lord Tennyson) and their modern-day counterparts—to investigate changing ideas over time about women and relationships.

I was very familiar with Fowles’s work, as one of my major papers for my MFA had been on it. In fact, I was on my way to stay in Lyme Regis, where the book was written, where its story supposedly takes place, where the movie (1981) was filmed, and where he was living at the time. Maybe I’d run into him at the supermarket. I ended up staying just below him on the hill overlooking the Cobb, but there were no sightings, and I was too shy to ask.

The painting on the cover is The Beguiling of Merlin—more commonly known as Merlin and Nimue—by Pre-Raphaelite painter Edward Burne-Jones. It took me a while to track down the original painting, which turned out to be in Liverpool, another of my future stops.

In Liverpool’s Merseyside National Museum, there’s a painting of Merlin, blank-eyed, his hands limp, his head on his shoulder as if falling asleep, his body slumped on the embankment. His pupil, Nimue, stands in front of him, looking back over her shoulder, in a purple gown so thin it ripples like waves across her thighs. In the uncertain light of the small museum, the wet material against her flesh could be leather or lizard skin. Like Botticelli’s Venus, her body is elongated, her neck and legs unrealistically stretched, her tiny head impossibly snakelike.

In Arthurian legends, Nimue is an obscure enchantress who was mistress to the prophetic poet Merlin. In Celtic tales, she is known as Rhiannon. Merlin fell in love with Nimue and taught her his secrets, although he knew that loving her would ultimately bring him to his end because he lived his life in reverse. When he had taught her all he knew, she used one of his spells to entomb him inside a boulder where he couldn’t move his fingers or mouth to reverse it.

The artist, Edward Burne-Jones, was in love with his model, the sculptress Maria Zambaco, when he painted her as Nimue and himself as Merlin, desolate and destroyed, behind her. [Nimue] is reading from a book of incantations and only for a moment pauses to look over her shoulder at Merlin, dissolving into clay.[3]

It was at least partially through my attempts to learn more about this painting that I came up with the first of my slide-and-text performances, “Ekphrasis and Cathexis,” which mixes a variety of sources—the letters of Héloïse and Abelard, the story of Emmy Hennings, “Beatlemania,” the Pre-Raphaelites and their lovers, with personal stories from journals and letters, and passages from other works—into a story that includes historical and semi-historical characters related obliquely to the central image of—in Leonard Cohen’s phrase—“The Absent Mare”—a longing for something not only out of reach but that perhaps does not exist.

Burne-Jones was one of the last of the Pre-Raphaelites. His mother died a few days after his birth, and his older sister died shortly thereafter. Following their deaths, his father plunged into a depression so deep he basically forgot about the boy.

As an art student, Burne-Jones was drawn to the melancholy attenuated figures of the fifteenth-century Florentine painters Filippino Lippi and Sandro Botticelli. In Burne-Jones’s later paintings, many of his feminine spirits—it would be incorrect to call them women—appear depressed, disconnected from self and surroundings, emotionally and physically out of reach beside disturbingly depressed and all-too-mortal men.

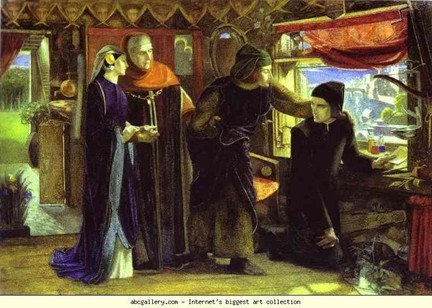

It was in 1856, upon first seeing Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s watercolor Dante Drawing an Angel on the First Anniversary of Beatrice’s Death, that Edward Burne-Jones decided to become a painter. In a way, the themes of Burne-Jones’s entire œuvre are rooted here. The grieving poet holds a drawing he has made of his lost love, while his reverie is unhappily interrupted by some townspeople who have arrived on official business.

Beyond the themes of melancholy and loss, we can recognize Burne-Jones’s elongated figures, confined composition, saturated tones, the blended beauty of medievalism and—at the time—modernism.[4]

Dante Drawing an Angel on the First Anniversary of Beatrice’s Death, D.G. Rossetti (1849)

In Rossetti’s painting, Dante refuses to acknowledge his guests. Burne-Jones would take his refusal one step further. “Whenever I hear the word ‘science,’ I shall paint another angel.”

In Pre-Raphaelite paintings, women are rare creatures, a feast for the senses, and a man’s reward and responsibility, inspiring greatness. They humanize, evolve, and tame their men. Their fragility calls out to be tended to, shielded, and shepherded.[5]

While in his teens, Rossetti founded the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and remained their remote and celestial inspiration, almost a muse, well beyond his death. He also painted his lovers, most memorably his wife Elizabeth Siddal as Beatrice. When Rossetti abandoned her as his muse for his best friend’s wife, she overdosed on laudanum, and Rossetti began to paint her again, this time obsessively. With each painting, she became an increasingly unattainable ideal. In her last portraits, she is almost transparent, overstuffed with light. Later, in a perverse twist to the story of Eurydice and Orpheus, when his addictions worsened and he stopped painting altogether, Rossetti became desperate for money and dug up Elizabeth’s coffin so he could rescue a manuscript of poems he’d wrapped in her hands before she was buried.

Beata Beatrix, D.G. Rossetti (1870)

The most famous painting of Siddal by Rossetti—painted in 1870, eight years after her death—is Beata Beatrix (Blessed Beatrice)—Dante’s Beatrice—at the moment of her death. The white poppy symbolizes the laudanum that was the cause of [Siddal’s] death. She is escaping her body as pure light.

It’s to the point that everyone who knew [Elizabeth] didn’t recognize her in the painting, even though Rossetti painted it not from memory but from life studies. He wrote to Morris that he intended the painting “not as a representation of the incident of the death of Beatrice, but as an ideal of the subject, symbolized by a trance or sudden spiritual transformation.”

Elizabeth had been a model for several Pre-Raphaelite painters before Rossetti married her and prevented her from posing for others. There are over 1000 drawings and paintings of Siddal in Rossetti’s hand. Her brother-in-law, William Rossetti, described her as “a most beautiful creature with an air between dignity and sweetness with something that exceeded modest self-respect and partook of disdainful reserve; tall, finely-formed with a lofty neck and regular yet somewhat uncommon features, greenish-blue unsparkling eyes, large perfect eyelids, brilliant complexion and a lavish heavy wealth of coppery golden hair.”

What makes Elizabeth’s later idealization by Rossetti and others surprising is that she was discovered at the age of 20 working in a London milliners by the painter Walter Deverell, who saw in her the perfect model of a peasant girl, plain and pliable. Ironically, the Pre-Raphaelites’ call to arms began with an insistence on painting real human beings, rather than the idealized or “antique” inhuman characters who appeared in most paintings at the time. Their religious and mythological paintings are revolutionary in that they painted actual carpenters and shepherds with individualized everyday faces and bodies.

Ophelia, John Everett Millais, 1870-71

The most famous of her portraits, other than Rossetti’s, is Millais’s Ophelia, painted at the moment of her death. In another terrifying irony, Siddal posed for the painting in a bathtub filled with water, heated by candles. When the candles went out, Siddal never complained. By the time Millais pulled her from the water, she was unconscious and nearly died.

In William Morris’s only completed easel painting, his wife Jane poses as La Belle Iseult, in medieval dress and apparently just risen from the twisted bedsheets, where a greyhound—a gift from Tristran, referred to in Malory’s Le Morte D’Arthur—represents her absent lover, who has been exiled by King Mark, her husband. She wears sprigs of rosemary—for remembrance—and “DOLOURS”—grief—is written along the side of her mirror.

La Belle Iseult, William Morris

It was painted by Morris in rooms he shared at the time with Edward Burne-Jones, who was engaged to Georgiana MacDonald, who would later become Morris’s lover. In another irony in a story saddened with them, it was painted at the time Morris’s wife was having an affair with Rossetti–La Belle Iseult redux–although Morris did not know it at the time.

Jane Morris

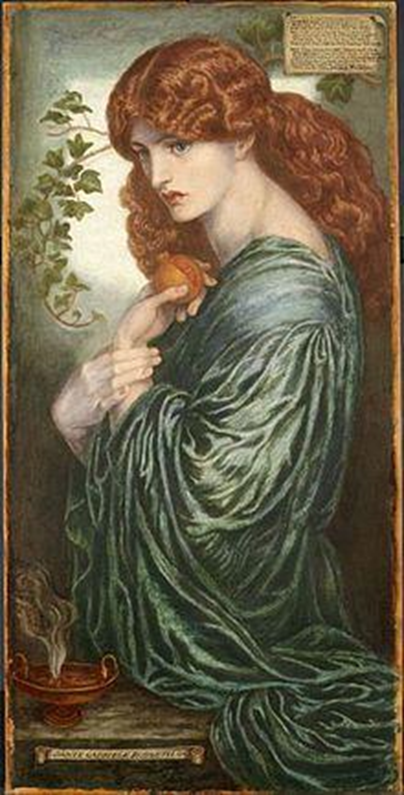

For Rossetti, [Jane] was more Persephone, a dark combination of goddess and femme fatale. In his photographs, she appears listless, sometimes draped over furniture, something of a nothing. By the end of his life (paralyzed and partially deaf at 54), Rossetti was consuming 180 grams of the hypnotic chloral-hydrate a day (at a time prescription levels ranged from 0.5-2 grams), washed down with straight whiskey. It was at this time he introduced Burne-Jones to a friend as “one of the nicest young men in Dreamland.”

Jane Morris as Proserpine, D.G. Rossetti (1880)

Proserpine, of course, is the Latin spelling for Persephone, the Greek goddess who—like Eurydice—was taken by death too young. “Rossetti painted it at a time when his mental health was extremely precarious and his love for Jane was at its most obsessive.”[6] Rossetti wrote of it:

“She is represented in a gloomy corridor of her palace, with the fatal fruit in her hand. As she passes, a gleam strikes on the wall behind her from some inlet suddenly opened, and admitting for a moment the sight of the upper world; and she glances furtively toward it, immersed in thought. The incense-burner stands beside her as the attribute of a goddess.”

Jane was imprisoned too—in a loveless marriage. She, too, had tasted forbidden fruit. He painted her lips the color of pomegranate, and behind her is an ivy, of which Rossetti wrote:

“The ivy branch in the background represents clinging memory and the passing of time; the shadow on the wall is her time in Hades, the patch of sunlight, her glimpse of earth. Her dress, like spilling water, suggests the turning of the tides, and the incense burner denotes her subject as an immortal. Proserpine’s saddened eyes, which are the same cold blue color as most of the painting, indirectly stare at the other realm.”

Also of interest in relation to the myth that inspired the painting is that over the seven years it took Rossetti to finish it, Jane lived at Rossetti’s Kelmscott Manor during the summer months and returned to her husband in the winter.

Rossetti—also a noted poet, of course—painted a sonnet on the frame about his distant, unobtainable love object, who he knew would never leave her husband and children for Rossetti.

Afar away the light that brings cold cheer

Unto this wall,—one instant and no more

Admitted at my distant palace-door

Afar the flowers of Enna from this drear

Dire fruit, which, tasted once, must thrall me here.

Afar those skies from this Tartarean grey

That chills me: and afar how far away,

The nights that shall become the days that were.Afar from mine own self I seem, and wing

Strange ways in thought, and listen for a sign:

And still some heart unto some soul doth pine,

O, Whose sounds mine inner sense in fain to bring,

Continually together murmuring)—

“Woe me for thee, unhappy Proserpine.”

Part III: “And still some heart unto some soul doth pine.”

In “Ekphrasis and Cathexis,” I write about first seeing the painting The Beguiling of Merlin by Edward Burne-Jones in the Liverpool Merseyside Museum.

How does anyone invest a painting with so much passionate detail, so much life? The artist, Edward Burne-Jones, was in love with his model, the sculptress Maria Zambaco, when he painted her as Nimue and himself as Merlin, desolate and destroyed, behind her. Her eyes are languid, liquid, leaking. Everything about her is water. She stands on the edge of water.

Standing on the edge of water is where Charles first encounters Sarah in The French Lieutenant’s Woman.

Burne-Jones would paint Merlin and Nimue in this pose many times throughout his career—the first in 1857 and the fifth in 1873. After his final version he collapsed and, unable to rise from bed, was nursed for several months by his wife Georgie (whose letters remain shimmering highwires of intelligence and tension), who was by then the lover of his best friend William Morris, husband of Jane Morris, who was by then lover, model, and muse for Dante Gabriel Rossetti.

We recognize the depersonalization of Sarah by calling her “The French Lieutenant’s Woman,” but in a twist that’s difficult to believe, her real-life counterpart had an even stranger fate.

In the Liverpool Merseyside Museum, the label identifies Burne-Jones’s model as Mary Zambaco. In a descriptive catalog for the Tate Gallery’s collection of Pre-Raphaelite art, her name is given as Maria Zambaco. Gay Daly, in her biography of the Pre-Raphaelites and their models, explains that she was born Maria, but Burne-Jones anglicized her name into Mary. In a biography of William Morris her name is given as Marie. The solution is clear: never read more than one version of any story.

Fowles described his main inspiration for The French Lieutenant’s Woman as a persistent image he had of the late-19th-century “Victorian” woman in the rustic “realist” novels of Thomas Hardy, whose last novel was published in 1895. The Pre-Raphaelites were an active movement from 1858 until the early years of the 20th century. In a nodding wink to the reader, one of Fowles’s codas has Sarah ending up in Chelsea, living with Dante Gabriel Rossetti.

Michelle Phillips Buchberger is critical of Fowles’s presentation of Sarah, and complains that in much of Fowles’s work “he portrays a fundamental binary between the male and female characters: the female characters act as an elite set of ‘creators’ or ‘educated, visionary’ characters who provide the facilitation for the social evolution ‘in existential terms’ of the male ‘collectors,’ whose traits are present in all of Fowles’s flawed male protagonists.”[7] The reference to men as “collectors” is a nod to the title and subject of Fowles’s first novel, The Collector, about how the Male Gaze ultimately kills what it loves and men become monsters when they seek beauty but cannot possess it.

Alice Ferrebe is less forgiving. Sarah is an unreal “violently fetishised and objectified ‘other,’ differentiated from the male characters like Charles”[8] by their spiritual, psychological, and sexual powers.

Magali Cornier Michael has written that Sarah is not a character but a plot device because the reader has no insight into her thoughts and motivations other than how the male characters interpret them. She sees Sarah as a representative of the persistent myths of the feminine as “a symbol within a male perspective on women.”[9]

“Who is Sarah? Out of what shadows does she come?”

That’s how Fowles’s narrator ends Chapter Twelve. He begins Chapter Thirteen even more simply: “I don’t know.” Yet, I believe it’s not enough to characterize her as a cypher or mythic representation (or misrepresentation) of “the feminine.” We know that she seriously considers suicide halfway through the book and why. The sagest male voice other than the narrator—the physician who has known her since she arrived—diagnoses her as someone who is in love with being a victim. She tells us she’s proud of being an outcast from a hypocritical and unjust society and she plans and plots to see Charles again although it could potentially ruin them both. We learn that she lied to Charles and why, that she intentionally misrepresented herself and her history to the townspeople and why, that she knowingly seduced and abandoned him, that she was strong enough to leave Lyme Regis and travel to London as a single pregnant woman, that she had the wherewithal to find a way to succeed there without becoming a prostitute or a suicide—the most common outcomes for a woman of her condition and station at the time—that she is confident and assured in her ability to successfully raise their child alone (by pretending to be a widow—another strategic lie). She chooses what happens to her in both endings in the film and in two of the three endings in the book.

What’s more mysterious to me is Charles’s response to Sarah. What kind of person in his position would fall in love with someone like Sarah—risking everything with little hope of success based on what he already knows? Grogan warns Charles that Sarah is probably insane. When she is fired for disobedience and prepares to flee Lyme, she leaves a note requesting to meet with Charles one last time before she leaves for London. Dr. Grogan warns Charles against the visit, referring to cases he’s encountered where a single woman in her situation has trapped a man by compromising him and then blackmailing him into marriage. Except for the blackmail and marriage part, a sharp appraisal of what’s about to happen.

Charles visits her anyway, and they end up in bed, where Charles realizes she was a virgin, that nothing she told him is true, that she intentionally deceived him, that he is her lover, she says, because she “willed it.” She cannot explain why she’s deceived him, but he decides he must do the honorable thing and marry her, even after she insists that will never happen.

At this point, Charles takes the evolutionary leap he’s been unknowingly seeking, facilitated by his contact with Sarah. He ends up in church, looking for quiet to digest what has happened. He decides that Sarah has shown him (“unblinded” is his word) that he could be as free as she is, that he can choose how he wants to live, especially now that he—like her—is disgraced and exiled from society.[10] He writes a letter to Sarah explaining that he will return to rejoin her once he has done the right thing and called off his engagement. (The letter does not reach her, although Charles does not know this until the end of the novel.)

When Charles returns from tearing up his future, Sarah has left for London. He assumes her fate will be no better than most and rushes off to “save her.” On the train, the narrator sits across from Charles and explains that he has lost control of his characters (their resistance to the author’s plans is a complaint from the beginning). He tells us he wanted Charles to return to Ernestina after his brief impropriety, humbled and appreciative of what he has. This—as many critics point out—would be the standard ending for such a book in the Victorian age. That’s ending number one: the conventional one. But about a third of the book remains.

Charles arrives in London, hires a private investigator, checks areas frequented by prostitutes—at the time, one out of every 60 houses in London was a brothel, a Shadow of the strict propriety of the Victorian Age)—looks for recently arrived governesses, advertises in the local papers. He hears rumors that single women have traveled to the U.S. to make a new start and sails west. Through his love for a girl, he escapes not only an impersonal future and the limits of his social class but also his family, Lyme Regis, Exeter, London, and eventually even England, something unimaginable in his previous life.

Two years later, Sarah is discovered living in Chelsea, London. Charles surprises her at home and is infuriated when she is unapologetic about abandoning him. It turns out she is living with Dante Gabriel Rossetti and works as a model for many of the Pre-Raphaelite painters. He cannot comprehend that she was aware he was searching for her but hadn’t responded, allowing him to suffer. True to his time, Charles is scandalized that she is involved with the disreputable, dissolute Pre-Raphaelites, jealous that she speaks of them with reverence, angry that she would choose someone depraved over someone with his breeding, someone who loved her enough that he gave up a prosperous future for a governess. At one point, he is so upset they scuffle, and she falls to the floor, which shocks and scares them both. When Charles proves he is fully prepared to storm off in anger and end their relationship, Sarah confides that she is raising their child. Ending number two suggests that Sarah and Charles have evolved enough to be willing to begin a life together without marriage, as equals, as a threesome.

Ending number three is the narrator’s and Fowles’s preferred one, which is presented in the book as the “practical one.” Charles realizes that he cannot marry Sarah, considering their past in Lyme and his recent broken engagement, but is offended that she prefers to remain independent and continue their relationship as lovers. As he leaves, he passes their daughter, but Sarah says nothing, and it doesn’t occur to him that it could be his child. The narrator tells us that he prefers this ending because it is the only one where Charles learns and grows, as Sarah has. He is inspired and prodded by her to discover faith in himself, especially when in opposition to everyone’s expectations. It’s also the only ending that doesn’t try to explain or reduce Sarah to a plot contrivance. Charles accepts that he does not—and will never—understand Sarah.

“Yes, I am a remarkable person.”

At a crux moment in the film, Charles tells Sarah that she is a remarkable woman, in a misguided attempt, I believe, to give her courage. Surprisingly, she looks at him and responds. “Yes, I am a remarkable person.”[11]

For me, this moment in the film belies any attempt to undermine Sarah’s portrayal as a fully realized character. She’s not a remarkable woman, she’s a remarkable person. Yet, I react to that scene (unfortunately from experience) as though Charles is trying to ensnare Sarah with his compliments—attempting to bestow value on her through his Male Gaze’s valuations—and could take it away if she disappointed him. Her response might be somewhat shocking unless you realize she is aware of what is happening and what it means because she is the remarkable person who has “willed it” and it has come to be, against the moral compass of the times and expectations of the characters and readers. And also, if we follow the conceit, the intentions and desires of the author. Charles and the author are like corks in her roaring rapids. Charles is the one exposed to the elements who needs saving. She knows he cannot bestow value on her, nor would she want him to if he could. Her remarkableness is something she has earned. It’s hers. It’s her. She’s the remarkable person.

To me, Sarah is a character much larger than a red-haired stand-in for the Pre-Raphaelite ideal of feminine beauty. If she’s a symbol of anything in the book and film, I see her as a stand-in for Charles’s Anima. As such, she embodies the subjective, personal nature of creativity, and its mysteriousness, which cannot be explained but only appreciated as, well, remarkable.

This personal and subjective nature of creativity is something available to anyone of any age and gender in any era, almost by definition. But, remaining true to its setting, as a Victorian man, Charles only knows how to assume the role of savior or provider, which does not interest her. He can’t conceive that Sarah doesn’t need saving, no matter how many times and how many ways she demonstrates it by her actions. Their relationship does become an agent for her eventual freedom and independence, but only because she takes the initiative and resolves to continue on her own.

Charles eventually concludes that Sarah does not need a savior—or his version of one—in one of three endings in the book, and it’s clear Fowles and the narrator consider this romantic ending a false one. Instead, for Charles’s evolutionary leap to be successful, he must live up to Sarah’s challenge. To “reach her” he must become his own agent for change, not half a person who requires a “muse,” who fulfills her function by inspiring him. He must not try to assume the role of her savior, but all his focus should be on becoming his own. To be her equal, he must be willing to abandon the need he feels to possess her, not because he’s forced to but because he realizes it’s not a good thing. For this he must open in the way she’s open and become closed in the ways she’s closed.

One of the best analyses of the character of Sarah as presented by director Karel Reisz is in an essay by Steven Gale, available on the John Fowles’s website. In it he notes how Streep, in one of her first leading roles, is presented “… along a tightrope between attraction and distance. Her facial features, from the right side fine and even, from the left plain and out of alignment, convey this duality in the smooth progression of a scene and draw attention to her performance. Whether it is a strange twitching of her nose and eyes when she removes her spectacles as Anna, thinking about her role, or an unexpected lunging swing around a tree trunk as Sarah, while she otherwise sedately relates her encounters with the French lieutenant, Streep’s performance offers little jars and interruptions, keeping her continually surprising and unpredictable to us and Charles.”

I particularly remember that swing around a tree. Streep lunges unexpectedly to the left, breaking frame. You—along with the DP—are surprised, and the camera—a second too late—lurches to the left as well, attempting to capture her movement and failing.[12] What this suggests is that for Streep and Reisz—and Pinter as well—Sarah is not opaque because of a lack of authorial understanding, but because the character herself is defined by her unpredictability—a particular woman, and certainly not meant to be suggestive of all women.

Gale also ably describes Charles’s and our first sight of Sarah in the film: “Sarah’s face, not conventionally pretty or glamorous but intelligent, damaged, and soulful, shows itself to Charles long enough for him to be smitten, before turning back to face the sea. The turn back to the sea, her body moving slightly before her face, suggesting that her eyes are slightly drawn to stay looking, accompanied by music that both challenges and entreats, is an image of mystery and intrigue that invites all who see it to want to know more about her.”

Rather than the blank and shallow cliché feminist critics see in Sarah, Gale believes there is more information than we realize about her as a woman in the film.

As Charles is drawn into Sarah’s world of drama and passion, the predicament of a single, educated woman such as her in society is subtly conveyed. The local doctor, Dr. Grogan, speaks of melancholia and committing Sarah to an asylum, and when we glimpse inside such a place, it is populated by unwashed women dressed in rags, hovering in corners, rocking and whimpering. The film shows that women suffered greatly under the practices of the day. One of his conversations with Charles takes place during a break from a bloody breech delivery, and we hear a woman’s screams from the next room throughout. This is not only a marker for the dangerousness of being born female in the late 19th century, but that her doctor feels comfortable taking a break to chat with a friend about a patient’s suitability as a romantic partner—characterizing her as “probably insane” when we are aware she’s not—while easily ignoring the agony of a woman he’s treating through a serious medical procedure.

Behavior like Sarah’s—involving fantasy, sadness, sexual appetite, and artistic thoughts—meant pathology and committal. Or prostitution. As Anna does research for her role, in particular the delivery of the line “If I went to London, I know what I would become,” she discovers the prevalence of brothels and prostitution in Victorian London. The reality for a woman like Sarah was that unconventional behavior would see her either in an asylum or on the streets. In other words, there are reasons Sarah’s character is hidden, why there is mystery surrounding her. She has her reasons.

As for Charles, his character’s evolution involves his growing awareness—through an overwhelming love of a woman—to extend himself, beyond the expectations of his gender and time and station. In this, Gale attempts to justify Charles’s desire to protect Sarah. He wants to protect her because he loves her and she is vulnerable and in danger. What he ignores is that he is in danger as well.

I’d offer Gale’s commentary to anyone who believes the character of Sarah is as insubstantial as her critics suggest. “It is ironic that, in order to gain [her] freedom [from society’s expectations of her], she ensnares and destroys Charles, and she does it so skillfully and with intelligent insight into how he will respond to every prompt she offers.”

That was then, this is now

In Pinter’s film script, the second and final ending is presented via the framing story of the actors playing Sarah and Charles—Anna and Mike. Their story parallels the characters they are playing, except that both are married. (Anna’s husband is even French.) If they were single and unattached like Charles and Sarah, there would be no problem in 1981’s London to pursue their mutual attraction. For the events in The French Lieutenant’s Woman to have comparable weight on its centennial, they would have to betray a partner—not an ethos—to find themselves in a situation comparable to Sarah and Charles.

Mike, the actor playing Charles, is betraying someone—his wife, Sonia. Anna’s relationship with her husband is both simpler and more complicated. They are individuals—they barely speak the same language, they live separately and rarely see each other—but more than once Anna chooses her husband’s company over her lover. She insists that this allows her to remain a “free woman.”

We meet the spouses at an awkward wrap party that Mike has Sonia host. For most of it, while his wife is entertaining his friends, Mike is trying to get Anna to choose him instead of returning to her husband. To escape him, Anna sits beside Sonia in the garden, knowing it’s the one place Mike won’t go. Anna compliments her on the garden. Gardening is her creative outlet, she tells Anna. As a mother, she stays home with the children while her husband travels the world, making films. Anna says that she envies Sonia’s nesting. Living in her home, tending her garden, surrounded by her family. (Anna is childless and she suggests that for her it’s too late.) Sonia says, wearily, “Don’t envy me.” Her happy home is an artifice. She has an unfaithful husband whom she is certain is seeing someone, although she doesn’t know who. It always happens, she tells Anna, when he’s on a shoot. This is the moment when Anna realizes the collateral damage caused by her affair and continues to distance herself from Mike. Meanwhile, the film within the film is coming to an end, and Anna has known from the beginning that she is going home with her husband.

There is an unspoken parallel here between the betrayed wife and the fate of Ernestina—Charles’s jilted fiancée. To be jilted in Victorian society is equivalent to being branded “The Scoundrel’s Woman.” Gale explains: “Similarly trapped is the spoiled Ernestina, who has nowhere to go when Charles breaks off their engagement. She tries to run out of the room and is faced by household staff, so she tries to run into the garden but finds herself in the conservatory, surrounded by barred windows. She is imprisoned in a world of archery and tea parties, home furnishings and social niceties, and to be a jilted fiancée is surely a disgrace from which she will not easily recover. Marriage, domesticity, and social convention seem to offer a thoroughly bad deal for women in the film, whether in the Victorian era or 1980s England.”

Mirror, mirror, in her hand

In almost a commentary on Berger’s notes on the significance of the mirror to a woman’s notion of self, the film opens with a shot of Meryl Streep in period costume, applying make-up. When she finishes, she is called to the set for the first scene of the film. In a nice touch, the film within a film is shot in sequence, allowing Charles and Sarah’s relationship to follow the same path as Mike and Anna’s.

The last time we see Anna is in the same mirror, but this time she is taking off her red wig and leaving it in the theater. When Mike arrives for their rendezvous, we hear her drive away. The film ends with a single word, as Mike calls out for Anna by her character’s name. The suggestion is that he was not in love with the woman, but the character she was playing. Either way, both are mysteries to him until the end and—we sense—out of reach forever.

Gale ends his essay by broadening his position to address the larger issues of the “Male Gaze” brought out by the film’s critics: “[The] film is also a powerful provocation to thought about the desirability of the enigmatic woman in patriarchy. It is Sarah’s fabricated identity as a fallen woman that entrances Charles and appalls her society, but it exists because of her need to hang her difference on something tangible. Her desire not to fit into the roles that society offers her requires that she find a home for her exceptionality. As a woman who simply requires a room of her own in which to create, and the freedom to be left alone to do so, she has to sacrifice a lustful Sir Galahad in order to satisfy her needs.”

Or, as Charles comments sadly when he visits Sarah in her studio in Chelsea and sees her accomplished pastels and drawings. “You have found your gift.” And it wasn’t him.

Part IV: “my name/just one on the list of the dead”

Emmy Henning’s entire Wikipedia entry reads [in 2017], “Emmy Hennings (born Emma Maria Cordsen, 17 January[14] 1885-10 August 1948) was a performer and poet. She was also the wife of celebrated Dadaist Hugo Ball. Despite her own achievements, it is difficult to come by information in English about Hennings that is not directly related to her relationship with Hugo Ball.”

In the first sentence, we learn that her birth name has been replaced by a pseudonym, although we are not told why. The second sentence says she is primarily known—despite being a “performer and poet”—as the wife of a more famous artist. The third contains no information at all, underlining the fact that Hennings has been all but erased from the record “despite her own achievements.” Her story could be another ending to The French Lieutenant’s Woman—what if Sarah hadn’t turned away her Hugo Ball and “found her gift”?

My obsession with a photo of Emmy Hennings began during another haphazard pilgrimage in late summer 1990 from the Shakespeare and Co. bookstore on the Seine to Liverpool’s Merseyside Museum to see the painting of Merlin and Nimue I’d been struck by on the cover of Possession. When I returned to London, I tried without luck to find more information on the painting in the Reading Room of the British Museum. On my way out, my eye caught a photograph of Johnny (Rotten) Lydon—lead singer of the mid-’70s punk rock band the Sex Pistols—on the new arrivals’ shelves. I paged through it at random. It presented the punk rock movement as the most recent manifestation of a long history of European anti-art movements, beginning with the Dadaists, evolving into the Surrealists, the Situationists, and other cranks. I turned a page and was faced with a full-page photograph of Emmy Hennings.[15] I wrote about our “meeting” in “Ekphrasis and Cathexis.”

In August 1990, I came upon a white-bordered photograph of Emmy Hennings in the Reading Room of the British Museum. Hennings was mistress and later wife of Hugo Ball, the brilliant Dada poet. The photo was taken in Munich in 1913, three years before they would open the Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich.

It is June 1916. Hugo Ball appears at the cabaret dressed in a cardboard papal costume of blue tubular legs, scarlet-gold wings, and a tall, striped stovepipe hat. While reading “Karawane” and other “nonsense” incantations, Ball experiences a sudden panic. He no longer recognizes his surroundings, his friends, or his libretto. Struggling to finish (the rigidity of his costume necessitates that he be carried offstage), Ball hallucinates that he is preaching from an altar and falls into the Catholic rhythms he’d learned as a child.

jolifanto bambla o falli bambla

großiga m’pfa habla horem

egiga goramen

higo bloiko russula huju

hollaka hollala

anlogo bung

blago bung blago bung

bosso fataka

ü üü ü

schampa wulla wussa olobo

hej tatta gorem

eschige zunbada

wulubu ssubudu uluwu ssubudu

–umf

kusa gauma

ba–umf

As he speaks, he feels physically lifted out of his body into a different universe, where he understands everything all at once. By 1917, the Cabaret Voltaire is closed. Within three years, Ball returns to the church and Hennings follows, more Héloïse than ever.[13]

Halfway through “Ekphrasis and Cathexis,” I pause to define cathexis as the experience of a sudden unexpected “meeting” that one knows is significant—that something has shattered or come together, without knowing why—to explain my “meetings” with Emmy Henning’s photo, the painting of Nimue and Merlin, and Charles’s first glimpse of Sarah on the Cobb.

Sigmund Freud coined the term cathexis. One evening you’re at a party and you stumble into a conversation with a stranger, and there’s a vividness to the interaction that catches your attention. You feel them through what seems to be an energy exchange that flows back and forth as attention and feeling. The party recedes as they come into focus. It’s not something you’re doing—it’s happening to you.

This is what Freud calls cathexis—having your self-awareness splintered by unexpected experiences that break the continuity of your consciousness. You wake up in the dark, did you hear someone downstairs? Generally, your continuity of consciousness will continue until you get into a serious accident, have a life-threatening illness, hit bottom, lose a child, or meet an immovable object where you have no choice but to surrender.

In social interactions, cathexis happens when you feel yourself expanding and opening in someone’s presence. When it’s reciprocal, you feel challenged and witnessed. The moment seems heavy with significance and possibility, excitement and fear. Part of you wants your safety back.[16]

Cathexis is another word for being alive. The opposite is Thanatos, or the death wish, which wants to avoid the anxieties of life. We don’t really like being alive. We don’t like mortality, we don’t like continually stepping into mystery. Our obsession with order is our desire to be dead. We prefer to go through life on an even keel, to reach for the pen without having to look, spending our days half asleep.

Like Nimue in Burne-Jones’s painting, Emmy Hennings looks back at her lovers, me in this case.[17] Her shoulders are drawn back, her arms close to her body, her posture relaxed, poised as if she’s looking for the wings she knows are there but no one else can see. Or maybe she’s uncertain—are they still there? After all that’s happened?

She’s worn black again, black as her hair, black as the lines she’s drawn so carefully above her eyes. Hugo Ball compared her ghostly face to the human skull he carried in his pocket. He painted the skull’s cheekbones with roses and forget-me-nots. “Her living head reminds me of that dead one. When I look at her I want to paint flowers on her hollow cheeks.”

From a review of her 1912 cabaret show, I discover her hair was yellow and that she wore—unheard of in her time outside the red-light district—a minute dark velvet dress. She’s described as “hysteria itself,” “hypnotizing with morphine absinthe,” “a violent distortion of the Gothic.” It argues, ironically, “A woman has infinities but one need not confuse the erotic with prostitution.”

I don’t believe the reference to morphine absinthe is accidental. Her first collection of poetry—published in 1913, when she was 28 years old—was Ether Poems. The title is likely descriptive of her creative process. In one of them—“Ether Stanzas”—she writes almost wistfully of a Sarah-like retreat. But not to create art—rather, to dream.

Crowds collect in the Gare de l’Est

where bright silk banners wave as well.

You won’t find me among them, though.

I’ve run off to this vast big room.

I mix myself in every dream,

a thousand looks and each I know. (tr. William Seaton)

Variations of the word “morphine” appear regularly in her poems—including the title of one—“Morphin”—a word that, in true Dada spirit, is instantly recognizable and yet does not exist in any language.[18]

Absinthe was the alcoholic drink of choice (90-148 proof) in the artistic circles of the early 20th century. It consisted of anise, wormwood, fennel, other medicinals and botanicals, and was banned worldwide in 1915 as a dangerous hallucinogen. Most of the painters and writers of the time were stoned on absinthe regularly, including James Joyce, Vincent van Gogh, Baudelaire, Verlaine, Rimbaud, Picasso, Modigliani, Toulouse-Lautrec, Satie, Edgar Allen Poe, Lord Byron, Aleister Crowley, Alfred Jarry, and Ernest Hemingway.

There is much more information available on Hennings today [2017] than there was in 1990, when I wrote, “In the Dada programs from the years 1915 to 1920, Henning’s name is always listed as performing ‘Silence.’ But some traces of her exist, such as ‘Prison,’ a poem from 1916.”

We pull ourselves toward Death with the cord of hope.

Ravens are envious of our prison yards.

Our never-kissed lips quiver.

Powerless solitude, you are magnificent.

The world lies outside there, life roars out there.

There men are permitted to go where they like.

Once we belonged to them.

Now we are forgotten and presumed dead.

At night, we dream of miracles over our bare beds.

During the days, we move like frightened Animals.

We mournfully look through the iron railings

And have nothing left to lose

But the life God gave us.

Only Death lies in our hand.

The freedom no one can take from us:

To go into the unknown land.—tr. Steve Smith

Most of the “new” information available on Hennings is painfully second-hand. It’s well known that she coined the term Dada while building a Catholic shrine in her apartment, but I’ve learned that beyond “silence,” she also acted, danced, and puppeteered. Her paintings were hung beside Arp’s and Huelsenbeck’s in Zurich galleries. In one charming photo, she’s telling fortunes as a large arachnid.

The Zurich Post, 1915, reports she “was admired by expressionists as the incarnation of the cabaret artist of her time. The shining star of the Voltaire.” There’s a passage in a 1916 poem by German expressionist poet and novelist Johannes Becher that’s almost a crush note.

It was in Munich, at the Café Stefanie,

Where I recited for you, Emmy, poems

That I dared tell only you.—tr. Steve Smith

But as new translations of her poems appear, they only serve to reinforce my feeling that something is desperately wrong. I have yet to find a poem of Hennings that does not contain at least one variation of the word Tod—“death” in German. It’s likely things hadn’t changed much only a decade or two after the events of The French Lieutenant’s Woman. Gale’s description of the dangers threatening women like Sarah would apply to Hennings. According to records of the time, any woman exhibiting desire for personal fulfillment beyond being a wife and mother, exhibiting a sexual appetite outside of her husband’s needs, or expressing unconventional or “artistic thoughts,” would be considered pathological and possibly committed. Once committed, she’d lose all her rights, her marriage, and any future outside an institution.

William Seaton, translator of “The Dancer,” writes: “In her poems a malaise, a conviction of some intolerable derangement in things is linked with a nearly desperate eroticism, yet expressed with redemptive poise and precision.”

Dancer

To you it’s like I’m marked, my name

just one on the list of the dead.

Too gone to sin in many ways,

I slowly drag through life’s old game,

anxiety in every stride.

My very heartbeat’s sick,

and it grows weaker day by day.

The angel of death now stands inside.

I dance until I’m out of breath—

I’ll soon be in my grave—

I know I’ll have no lover then—

so kiss me until death.—tr. William Seaton

She was in her mid-twenties when she wrote, “I’ll soon be in my grave.” Wrongly. Written about the same time, her poem “Untitled” ends with her suffering separated out carefully behind parentheses.

(I press the thorns into my heart

and then stop full of peace,

and I will suffer every hurt

it’s what is asked of me.)—tr. William Seaton

Seaton also makes her connection to the visual art of the time explicit: “Many of her lyrics seem in a way the bohemian counterpoint to George Grosz’s scenes of bestial carnality among the ruling class. With the world disintegrating, she too grasps after some version of love.” As for her performances, a wonderful but unnerving review was published in the Zurcher Post, May 7, 1916.

“The star of the cabaret, however, is Mrs. Emmy Hennings. The star of who knows how many nights and poems. Just as she stood before the billowing yellow curtain of a Berlin cabaret, her arms rounded up over her hips, rich like a blooming bush, so today she is lending her body with an ever-brave front to the same songs, that body of hers which has since been ravaged by pain.

Her name first appears in print in 1913. She is 28 years old and living in Munich, part of a circle of expressionist poets, playwrights, and novelists who perform at the Café Simplizissimus. Hennings sings cabaret songs and recites her own poems and those of her friends. Hugo Ball is described at the time as nothing more than “one of her lovers” during a time in which she was also the mistress of the most important German anarchist of the time, Erich Mühsam. A year later she followed Ball to Berlin, where she sang in restaurants and posed as an artist’s model. They fled the rise of nationalism in 1915, arriving in Zurich in May, penniless and living on charity. They decided to start their own performance space and opened the Cabaret Voltaire on February 5, 1916, financed by her turning tricks.

On poetry nights, Hennings sang popular songs, Chinese ballads, folk songs, and performed her own poems as well as those of other Dadaists. Her poems focused on “expressionist themes such as loneliness, ecstasy, captivity, illness, and death. Certain places—prisons, hospitals, cabarets, and streetlife—and afflictions—prostitution and drug addiction—recur again and again.” (Zurich Post, 1916). Prominent Dadaists associated with the Cabaret Voltaire—including Richard Huelsenbeck and Hans Arp—considered her the most mystically inclined in their group. However, Hennings had her intense conversion experience following Ball’s and became a deep believer in Catholic theology in 1920 (more Héloïse than ever). At that point she began to erase any record of her pre-conversion life. She lived the rest of her life as a recluse, honoring Ball and dismissing their association with Dada as “a youthful misadventure.”

The most important addition to studies on Hennings is the paper (available online) “Emmy Hennings: Star of the Cabaret Voltaire and Dada’s Mystic Mother,” by Crystal Hoffman (2010). It begins:

“I was introduced to the artist, poet, cabaret performer, chanteuse, dancer, and painter, Emmy Hennings, through the work of her much more easily recognized husband, Hugo Ball, who is widely regarded as the mystical founder of DADA. This is perhaps what she herself hoped for, as she spent the latter years of her life promoting him tirelessly and altering or writing out of her autobiographies any aspect of her life which would not coalesce with the Catholic mythology which she painstakingly constructed out of their lives together, a fact which she reluctantly admitted in a letter to Herman Hesse, her closest friend after the death of Ball. Hennings preferred to keep from history most of the creative work produced during her long career as a member of Munich’s and Zurich’s Avant-Garde inner circles, as it would unfortunately also reveal a long career as a morphine addict, prostitute, and hustler, who frequently promoted free-love, anarchy, and social revolution, and spent several stints in prison, at least once for forging passports for draft dodgers. For this reason, it seems that Emmy Hennings welcomed individual artistic anonymity in favor of becoming a footnote to Hugo Ball’s career.”

Hoffman uses contemporary diaries and letters to paint a portrait of Hennings during her association with the Cabaret Voltaire. In several ways, it seems like an alternate ending to The French Lieutenant’s Woman, where Sarah becomes a prostitute—as Charles and everyone predicted—but also the co-founder of the first anti-art movement, a performing artist, painter, singer, actor, and poet, and eventually a Catholic renunciate.

Hoffman again: “Hennings was a woman of contradictions that often seemed to exist in two worlds at once. Sabine Werner-Birkenback remarks in an essay on her writings from prison that this makes her a difficult individual to study in anything resembling a linear manner. Despite the fact that she wrote on and took an interest in politics and social criticism, when reading accounts by her male contemporaries she represented for many the furthest thing from worldly concerns: mysticism and holy fairy tales. She was the embodiment of childlike naiveté and purity, yet [Ball] relied on her to manage day-to-day finances of the cabaret and the Gallerie Dada, and occasionally make ends meet by working as a prostitute. She was a poet and a writer, but she and Ball claimed that their primary means of communication was not words, but instead a ‘secret’ and ‘silent’ language and shared dreams.

It is challenging to reconcile Hennings’s deep religiosity and—in Hoffman’s terms—her debauched lifestyle as a Dadaist.

Hoffman: “She managed, though not without significant pains, to lead a bohemian lifestyle, obviously believing in and practicing many of the central tenets of the most radical ilk of anarchists and expressionist artists and thinkers in Munich, while also having a deep and abiding faith in the Catholic tradition. The pain of carrying on with these conflicting lifestyles was, in fact, occasionally too much for her. About a week after her initial conversion [her lover] Mühsam writes: ‘Bolz just left. He tells horror stories of Emmy’s condition which has apparently deteriorated into complete religious madness. She condemns me and almost all of her other friends as heretics and hallucinates about the devil trying to drag her off.’ The way that she melded these opposing traditions was by consistently maintaining a mystic sensibility in all of her practices and interactions with the world, which necessitates being liminal in all things and crossing, breaking down, and blurring binary relationships. This manner of interacting with the world, as well as the psychic and spiritual dissonance which she occasionally felt are all apparent in her creative works, as well. You can see her artistic take on the popular mystic traditions of the period in her themes of transcendence; death and other forms of worldly escape toward salvation or enlightenment, such as drugs and dreams; the combining of opposites to find unity; and the blurring of and crossing of boundaries. Weinstein notes, for example, that many of her poems explore the theme of separation of mental life and physical body; however, when seen through a spiritual lens it becomes clear that these examinations are actually of spiritual release from the physical body, rather than release from mental activity.”

Why does the last half of Hennings’s life differ so drastically from the several dreamed up by Fowles for Sarah in The French Lieutenant’s Woman? One possible answer is contained in Hoffman’s essay. “She longed for the companionship of men, even when it did more harm emotionally and spiritually than it did good. She had more life experience packed into her short years than most of her companions could boast of, as a prostitute, drug user, shyster, vagabond, mother, and wife; however, she gave the impression of naiveté, simplicity, and of having a child-like nature. It was for these paradoxes that she was almost entirely erased from the history of the movement that she helped to found and largely inspired. It was for these paradoxes that she felt the need to spend the latter part of her life writing and rewriting her history and that of her savior and spiritual other half, Hugo Ball.”

Hoffman gives Greil Marcus the final word—quoting from the book that sent me on this pilgrimage.

“In Greil Marcus’s study of the 20th Century: Lipstick Traces, he notes that ‘Along with Hugo Ball’s drive to create, there was Emmy Hennings’s need to destroy.’ Add Marcus to the laundry list of men who have attempted unsuccessfully to simplify or make sense of Hennings’s role in Dada. Her contradictory existence could never be made sense of.”

Hennings died in 1948 in Magliaso, Italy. The last two decades of her life were spent in a tiny room above a grocery store. To survive she worked in a nearby factory. Like Héloïse, Hennings outlived her husband by 22 years.

Part V: “she was deep within herself”

Detail from poster for Eurydice, Sarah Ruhl, 2003

“Let’s go in the water.”

For Ovid, Eurydice is mostly a plot device. There is no acknowledgement of her inner life or agency. The other bloodless shades weep at Orpheus’s song, as do half a dozen recognizable characters in Ovid’s Underworld. These have all retained their full earthly personalities. They can act within restrictions and apparently have self-awareness. As for what we learn of Eurydice in the Underworld, when summoned by the two men who control her fate, “she obeyed the call by walking to [Pluto and Orpheus] with slow steps, yet halting from her wound. So Orpheus then received his wife.”

The journey out of the Underworld is told from Orpheus’s point of view—with Eurydice unacknowledged and silently following him—until they reach the surface.

He turned his eyes so he could gaze upon her. Instantly, she slipped away. He stretched out to her his despairing arms, eager to rescue her, or feel her form, but could hold nothing save the yielding air. Dying the second time, she could not say a word of censure of her husband’s fault. Her last word spoken was, “Farewell!” which he could barely hear, and with no further sound she fell from him again to Hades.

This is all we are told of Eurydice’s inner life. She didn’t hold a grudge that Orpheus caused her second and final death: “what had she to complain of—his great love?” The Male Gaze saves her, until it kills her.

In the millennia since Ovid, you could fill a library with tales of Orpheus. Yet Eurydice has mostly retained her silence. There are a few sculptures and a handful of paintings that she doesn’t share with her husband. Paintings and sculptures entitled simply Eurydice all focus on her death and the snake. She is no more a shade at the end of the story than she was from the first.

But there are two modernist exceptions. The fullest retelling of her tale is by Sarah Ruhl, a playwright who—while in her mid-thirties—had already been nominated twice for a Pulitzer Prize [The Clean House, 2004, and In the Next Room (or the Vibrator Play), 2009] and received a MacArthur Fellowship in 2008. At the age of 42, she was awarded the 2016 Samuel French Award for Sustained Excellence in American Theatre.

This was not Ruhl’s first retelling of an ancient Greek myth that involved a young woman taken by death in the bloom of youth. In both Ovid and Ruhl, Persephone is “rescued” by her mother. Ruhl’s retelling—Demeter in the City—premiered in 2006 and modernizes her story into “an urban tale in which ‘Dee’ loses her parental rights once the city discovers that her idea of a little ‘me time’ involves opiates and needles. By the time the story plays out, the child [Persephone] is lost not once but twice” (Wenzel Jones, L.A. Times, 6/15/06).

Ruhl’s Eurydice (2003) is a modernization of its tale as well, with significant differences from the story as told by Ovid and others. In her performance notes she writes: “Eurydice and Orpheus should be played as though they are a little too young and a little too in love. They should resist the temptation to be ‘classical.’ The underworld should resemble the world of Alice in Wonderland more than it resembles Hades.”

Ruhl describes her theater work as pre-Freudian and closer to the way the Greeks, the medieval world, and Shakespeare understood the humors, melancholia, and transformation. She intends her plays to evoke specific emotional states [humors—melancholia, etc.] through ritualized performances, and then provide catharsis—the term introduced by Aristotle to describe the psychological healing possibilities of theater.

She dedicates the play to her father, who died when she was twenty. She was married shortly after the play premiered, which adds poignancy to the scene where Eurydice’s father in the Underworld walks her daughter down the aisle in his imagination. Ruhl explained in an interview in 2007 that when he died, the only outlet she had to deal with grief was therapy. “Why should [the natural grief of an unmarried daughter for a father who died too young] be pathologized? We’re all going to do the dying thing someday. It felt like there was no cultural ritual to organize my feelings. Theater became that for me.”

Ruhl and her father shared an interest and love for language, and in revisiting the play we can see how, in her own words, the play was a way to “have a few more conversations with him.” Each Saturday, from the age of five, her father took his daughters to the Walker Brothers Original Pancake House for breakfast and taught them a new word, along with its etymology. In the play, she lovingly recreates those language lessons, including several she remembered 30 years later—“ostracize,” “peripatetic,” and “defunct.”

Into the water

As the play opens, Eurydice and Orpheus—dressed in 1950s-style bathing costumes—are sitting on the beach on the eve of their wedding. Orpheus is giving her gifts. All the birds. The ocean. The sky and the stars. She asks him what he’s thinking about. “Music.” She questions whether you can think about music—you either hear it or you don’t. “Then I’m hearing it.”

She tells him she has been reading an interesting book—she doesn’t give the title, but it could be Ovid’s Metamorphoses, or more likely the Complete Works of Shakespeare, which makes an appearance later in the play. She describes it—I believe intentionally—in such a way that it could be either. “There were—stories—about people’s lives—how some come out well—and others come out badly.” He asks if she loves the book, and she says yes, she thinks so. “Because it makes you—a larger part of the human community.”

Seemingly jealous of her love for the book, he tells her he has written her a song and ties a string around her ring finger. She asks if this means what she thinks it means. He says, “I guess so.” So much for his romantic reputation. He can’t even propose to her and the word itself is never spoken, but he expects all the benefits of marriage in return for the promise of a golden ring in the future, which—spoiler alert—never materializes.

She decides it’s time to “go into the water.” As they walk, he tries to teach her one of the 12 parts of her song, but she is not a skilled singer and cannot remember the melodies.

ORPHEUS: I’m going to make each strand of your hair into an instrument. Your hair will stand on end as it plays my music and becomes a hair orchestra. It will fly you up into the sky.

EURYDICE: I don’t know if I want to be an instrument.

ORPHEUS: Why?

EURYDICE: Won’t I fall down when the song ends?

ORPHEUS: That’s true. But the clouds will be so moved by your music that they will fill up with water until they become heavy and you’ll sit on one and fall gently down to earth. How about that?

EURYDICE: Okay.

Scene Two begins in the Underworld. It’s the same set, except for the presence of three stones (named in the script Little Stone, Big Stone, and Loud Stone). These essentially function as the chorus in Greek drama, and it’s a witty conceit to turn them into stones since, like the original choruses, they can only comment omnisciently on the play as it unfolds but are unable to act or influence the course of events. What the Stones mostly have to say is “Shut up, Eurydice, and get used to being dead.” Whenever she struggles, they are there to tell her that death is easy if you welcome its forgetfulness. She is constantly being told to keep quiet by everyone except her dad even in the Underworld.

Eurydice’s deceased father is writing a letter to his daughter on her wedding day. “There is no choice of any importance in life but the choosing of a beloved. I haven’t met Orpheus, but he seems like a serious young man.” He lists his fatherly advice for her.

Cultivate the arts of dancing and small talk.

Everything in moderation.

Court the companionship and respect of dogs.

Grilling a fish or toasting bread without burning requires singleness of purpose, vigilance, and steadfast watching.

Keep quiet about politics, but vote for the right man.

Take care to change the light bulbs.

Continue to give yourself to others because that’s the ultimate satisfaction in life—to love, accept, honor, and help others.

“Everything in moderation” is, of course, one of the two sayings carved on the lintel above the main entrance of Apollo’s Temple in Delphi. The adage her father avoids is the one that might have helped. “Know thyself.” It’s also notable that in a play written by a woman in 2004, the genius father advises his daughter to vote for the right “man.” He then explains what it’s like to be dead.

As for me, this is what it’s like being dead: The atmosphere smells.

And there are strange, high-pitched noises—like a tea kettle always boiling over. But it doesn’t seem to bother anyone. And, for the most part, there is a pleasant atmosphere and you can work and socialize, much like at home. I’m working in the business world, and it seems that, here, you can better see the far-reaching consequences of your actions.

Also, I am one of the few dead people who still remembers how to read and write. That’s a secret. If anyone finds out, they might dip me in the River [Lethe] again.

He ends the letter by reminding himself that he has no way to get the letter to her, and signs it “Love.” He pretends to drop the letter into a mail slot, but it falls to the floor.

It is Eurydice and Orpheus’s wedding day aboveground, and her father can see everything from the Underworld. He pretends to hold her by the arm to walk her down the aisle, nodding and smiling. He gives her away and begins to cry.

After her father leaves for “work,” the letter is found by a character whose name is given in the script “Nasty Interesting Man” (who turns out to be Pluto, the Lord of the Underworld).

Aboveground, Eurydice steps out for a bit of quiet and solitude after her wedding. She meets Nasty Interesting Man, who tells her of the letter from her father. She follows him to his apartment, where he tries to seduce her. She flees without the letter, tripping and falling to her death on the stairs.

Eurydice arrives in the Underworld via an elevator. When the door opens, it is raining inside, perhaps inspired by Dali’s Rainy Taxi. “What happiness it would be to cry,” she says, but it becomes apparent that she has lost not only her memories but the emotions that are built on them.

She is discovered by her father, whom she mistakes for a porter. She believes she has arrived at a hotel. That would be the deepest forgetting, to not recognize the father you adore. That would be the gravest blow in being forgotten, when the person you love above all others mistakes you for a porter. For the theatergoer, it’s a reversal of the madness of Lear and his reunion with Cordelia.

Not wanting to disappoint her, he builds a room out of string. Gradually, he teaches her language, and each new word becomes a piece of the world they are reconstructing from his memory. He begins by teaching her his name, her name, and her husband’s name. It is the birth of identity and all that implies. Then he begins to recreate her past, memory by memory.

She questions restoring memories of her difficulties, losses, pain. But—as opposed to the pleasures of forgetfulness the Stones advise—her father tells her it’s important to appreciate the full beauty of life, love and its loss, transience and its pleasures, difficulty and the triumph over difficulty. It’s all sacred, he tells her, when seen from down here.

Orpheus writes a letter to Eurydice, which flutters to the Underworld. Her father finds it and reads it to her. Orpheus is searching for her and will travel all the way to hell if necessary to bring her back. He also sends her the Complete Works of William Shakespeare, attached to a long string. She does not understand the word “book,” so her father opens it at random and reads: “Come, let’s away to prison;/We two alone will sing like birds ‘i th’ cage.” This, of course, is from the scene when Lear and Cordelia are reunited. Lear, this close to the end of the play, is still living in a fantasy that he and his daughter will live happily ever after. His romantic dreams hide him from the danger that approaches. Within minutes, both he and Cordelia will be dead.

Orpheus arrives in the Underworld, singing a song that makes the Stones weep, which is traditional. He is greeted by the Lord of the Underworld, who gives him the standard instructions: he can have Eurydice back if he doesn’t turn around before she’s aboveground.

Eurydice is torn. Her father has told her that she is the wife of this Orpheus, so he must be her husband, although she doesn’t recognize him. She has no feelings for this musician, but her father is her father, and she is filled with feelings for him because he has taught her about life, returned her memories, given her love. Her studies have taught her that the upper world knows only imperfect love, struggle, and sorrow, but in the Underworld she is beyond sorrow and struggle and has been reunited with the man who taught her what love feels like. Here they will never be separated, never again will she experience loss. Why would she want to go back to grief and suffering, abandon the father she loves, she asks.

Because her loyalty must be to life, not to him. He will always be her father, but it’s nature’s way for a daughter to leave her father for a husband. Walking away from one’s father is the first of many changes that lie ahead as a daughter becomes a woman. He insists she choose life and live fully until it is her time. They’ve had more time together than they expected. Now it is time to discover her own life, start a family, teach them as he has taught her. That’s the cycle of life, and it will continue as long as life continues. They will rejoin in the Underworld all too soon, for all time.

Eurydice reluctantly follows her father’s advice, but as she nears the surface, she calls out to deceive Orpheus, causing him to turn around, sending her back to the Underworld.

When Eurydice finds her father, their situations have reversed. Who she adores above all others doesn’t recognize her. The Stones tell her that, unable to tolerate losing her, he erased his memories—including language—by dipping himself in the Lethe.

The Nasty Interesting Man returns, by now having grown into his true stature as Pluto, King of the Underworld. He orders Eurydice to be his bride, his Persephone, Queen of the Underworld. She puts him off long enough to write a letter to Orpheus and his next wife, relieving him of his love and asking that they live fully for her sake. Then she enters the Lethe and floats into forgetfulness. The elevator opens and Orpheus appears. He finds Eurydice’s letter, but cannot read it, and does not recognize her.

He has written her a song

In reviewing their opening conversation, we overhear a young couple navigating personal space. He’s a musician—in other words, Dionysian. She’s Apollonian—she loves books.

On their walk to the beach, he tells her that he has written her a song, then requests that she learn one of the parts to take some of it off his mind. He tries to teach it to her, and—as she is not musically gifted—criticizes her abilities. This will be contrasted with the way her father teaches her. That’s okay, he says—assuming her role in service to his artistic vision is a given—they will practice. In a bit of tragic foreshadowing, he asks her if she will remember his song even when she is “under the water.”

He tells her that he will turn her into an instrument on which to play his songs—a sharp commentary on what would become of her in her own story, especially the prescient line, “Won’t I fall down when the song ends?” He marries her with a piece of string and then declares their life together will be Dionysian, filled with music (i.e., not books).

The multiform and multiple uses of string become another thread throughout the play, like the gift of Ariadne, another besotted lover about to be destroyed by her man. Orpheus uses string to “tie her down” in marriage. The house her father built for her is no more than string. An unexplained string is attached to the Complete Works of Shakespeare. Ruhl may be using string as a physical reminder of the “ties that bind,” including perhaps the most powerful, a father’s lifelong compulsion to protect and nurture his daughter. But also a daughter’s duty to her father, a husband to his wife, a wife to her husband, and our allegiance to what is closest to our hearts, in her case books and drama. Also implied are the other ways we bind and are bound, exemplified by a husband who ties his wife to him as property.